I’m tired of hearing, “He was a good pilot. How could that happen?” No, I’m not just tired, I’m mad when I hear that after a pilot dies in a maneuvering accident.

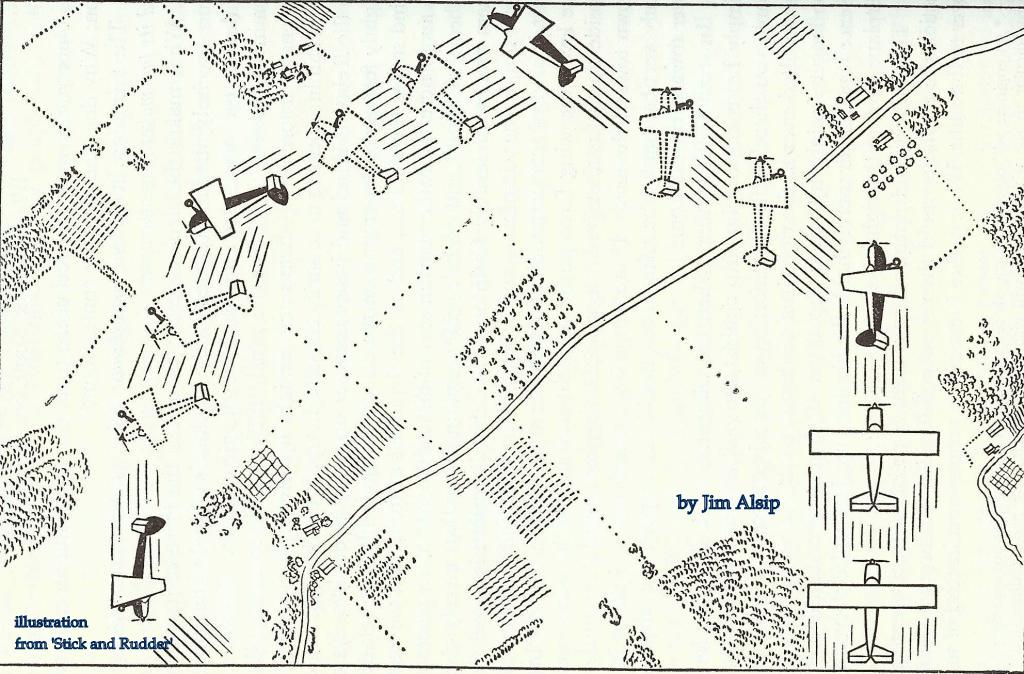

It seems that all thoughtful professionals involved with flight training and the promotion of aviation safety lump the issues of controlling the airplane under the category of “stick and rudder skills.” Pilots, flight instructors and media pundits have pontificated on their importance for decades. They say we must do better, yet nothing is changing; pilots are still dying.

I propose a simple message, profound and based upon the fundamental principles of flight. I argue that if pilots are taught to master the turn they will avoid loss of control. Mastering that simple skill will save lives.

The turn is the definitive maneuver that builds stick-and-rudder skills and teaches emergency attitude recovery. That’s because it requires three key elements of maintaining control: the use of sight picture; avoidance of back elevator pressure; and control of adverse yaw.

Statistics and anecdotal evidence suggest we are not teaching pilots to turn an airplane properly. We must change the way we teach that skill. I argue that some of what we teach represents a primary factor in loss of control accidents. Students deserve better. Pilot school (and the FAA PTS) must emphasize the two fundamental principles of flying an airplane: do not stall; and control yaw. Keep it simple; demonstrate; and actually teach the elements of a turn:

Key Points:

- Teach pilots to fly with “hands off’ the controls. Begin with trim. An airplane should always have power and trim set to maintain the desired flight path (climb, level, descend) and airspeed. Properly trimmed and powered, an airplane will fly most maneuvers without continuous over controlling inputs by the pilot.

- Use rudder to control adverse yaw. Roll into a moderate bank of 25 - 30 degrees. Please do not tell the student to “coordinate the turn.” That is not instructive. Teach them to control adverse yaw. Show them how to use cadence to coordinate rudder and aileron. Please do not tell them to “step on the ball.” That is closing the door after the dog goes out.

- Once established in the bank, aileron and rudder are neutral. Allow the horizontal component of lift to push the airplane through the change in direction. During turns at moderate bank angles, a pilot should be able to remove hands and feet from the controls with the airplane maintaining a constant bank angle and holding altitude all by itself.

- The elevator is neutral when rolling into and out of a bank. This is huge! Almost universally, pilots apply and hold back pressure every time they use aileron. I suggest that comes from pilot school obsession with maintaining altitude. If needed at all, use the elevator only “in” the turn; not when rolling into and out or the turn. (Many pilots are shocked when they discover a moderately banked level turn, free from adverse yaw and with neutral elevator, does not lose much altitude.)

Pilots become flyers when they learn to use the sight picture to manage attitude. The discipline to focus on sight picture and to avoid head and body movement promotes a light touch on the controls, free from over-control and pilot-induced oscillation. A properly executed level turn (especially when practiced with a fast roll rate) demonstrates that a pilot has mastered these two fundamentals that will lead to a better safety record:

- Do not stall

- Do control yaw

Emergency situations:

If we actually teach pilots to turn an airplane properly, they will develop the habit of using “top rudder.” In an emergency, that reflex, that habit, the automatic response becomes a life-saving maneuver: neutral elevator, top rudder and top aileron. Military fighter pilots learn this. Let’s spread the word – developing that habit will save a life.

- by Jim Alsip – Master CFI-Aerobatic; SAFE Charter Member; FAA FAASTeam representative.

- Jim Alsip’s most recent book is Artistry of the Great Flyer – A Pilot’s Guide to Stick and Rudder and Managing Emergency Maneuvers. Jim is a Master CFI-Aerobatic, a charter member of SAFE, and a FAASTeam representative in the Vero Beach, Florida chapter. Jim has years of experience instructing pilots in an airplane with tandem seating. His greatest insight as an instructor is watching where a pilot is looking during maneuvers; having learned that the head and visual focus control the body, Alsip can see what the pilot is missing. In his book, Alsip highlights stall, upset, and spin recovery along with rudder fundamentals that will save a pilot’s life. Learn more about Jim Alsip and all of his book and DVD titles at his web site: www.dylanaviation.com.