How many times have you read a checklist with Carburetor Heat “APPLY” or “ON” as one of the tasks that should be accomplished during preparation for landing? And during basic training we were reminded to check Carb Heat “ON” as one of the troubleshooting items during the simulated engine failure practice. The landing scenario is better understood than the engine failure application. More on that later.

For most of us, these two rote procedures were the extent of our training and knowledge of carburetor heat. If you trained in an airplane other than a Cessna or Grumman Tiger you may not have been exposed to the use of carb heat at all. For some students, the instructor might have included a simple explanation of how the warm air under the cowling - usually from the exhaust manifold or the muffler, often referred to as a “heat muff,” got to the carburetor. Beyond this there was little talk about carb heat.

Landing: There is no question that – due to the design of the air intake on a lot of planes - the use of carburetor heat is critical to safe operations before the power is reduced below normal cruise power, (the green arc on the tachometer). Notice, I said, “Before the power is reduced” – not after reduction. Since the commonly accepted purpose of carburetor heat is to prevent or remove ice from the carburetor throttle valve, it needs the heat produced by an operating engine. Even the reduced power setting used in the traffic pattern will usually produce enough engine heat to keep the carburetor sufficiently warm to prevent ice in most situations. However, in preparation for a descent or to set up for a landing, a greater power reduction is required and consequently the air temperature drops dramatically inside of the carburetor making ice formation that much more likely. Therefore, carburetor heat must be applied before power is reduced from a cruise or low cruise setting. It takes about 30 seconds for the carburetor heat to be effective.

Engine failure: OK, enough said about the most common use of carburetor heat. But what about a use that is equally important? When practicing a simulated engine failure, the pilot will go through the routine of establishing glide speed, looking for a place to land, enriching the mixture, changing fuel tanks, applying carburetor heat, etc. I have noticed that – almost without fail — when I ask the pilot why we open the carb heat after the power loss the answer will be, “well, to get rid of carburetor ice.” Then I ask, “Do you really believe that if there was enough carb ice to cause engine stoppage that this now silent engine is going to provide enough heat to melt that much ice?” With some thought they answer, “I guess not.” Well, then why is this action near the top of the “Engine failure in flight” check list?

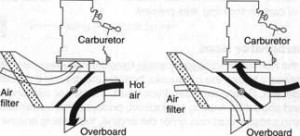

Occasionally someone gets it right. Opening the carb heat will provide an alternate air source to the carburetor in the event that something blocked the air intake. Perhaps a bird blew into the plane and lodged itself in that small opening in the cowling that directs outside air to your carburetor. Whether the plane is a Cessna with a direct path from ram air to the carburetor or a Piper product where the air is routed around indirectly to the carburetor, something could block the air inlet and cause engine stoppage. We have the cure readily at hand. The Carburetor Heat.

Occasionally someone gets it right. Opening the carb heat will provide an alternate air source to the carburetor in the event that something blocked the air intake. Perhaps a bird blew into the plane and lodged itself in that small opening in the cowling that directs outside air to your carburetor. Whether the plane is a Cessna with a direct path from ram air to the carburetor or a Piper product where the air is routed around indirectly to the carburetor, something could block the air inlet and cause engine stoppage. We have the cure readily at hand. The Carburetor Heat.

-by Jean Runner